That Time I Worked At NASA (and didn't steal anything)

Why my NASA experience made it so hard to write about someone elses.

It was the summer of 2012 when I started working at NASA.

And yes, it was as cool as it sounds.

I’d moved to a grubby little AirBnB room in a scenic part of San Francisco, and every day took the thrillingly rickety BART subway to the main station, before and Amtrak train down to Mountain View. I always sat on the upper level, a novelty not afforded British train passengers, and I marvelled at just how slowly the train travelled. It took an hour to travel the length of San Francisco Bay.

Outside the Amtrak station, the tree-lined avenue was warm with reflected sunshine, and it smelled of orange blossom. I followed the crowd of men and women (mostly men, let’s be honest) to the tidy row of yellow schoolbuses, and scanned the destinations. Apple. Google. NASA. In that moment, falling in step with the ranks of Silicon Valley hotshots, and stepping onto my NASA bus, I couldn’t quite believe my good fortune.

Sure, I’d worked hard for it - I’d submitted my 350 page DPhil thesis just a month earlier, published papers, applied for and been awarded grants, and impressed a panel of interviewers enough to be granted this prestigious planetary internship at NASA Ames. I was about to spend the next few months working on an experiment of entirely my design, which I hoped would pave the way for future discoveries of ancient extraterrestrial life. Ancient aliens, if you will. I guess from the outside you could say I’d earned my place on that bumpy bus, passing underneath the NASA logo into the Ames campus, but I still felt like little old me being handed a dream on a platter. As we waited for the security gates to lift, I pinched myself. I had arrived.

Over the next few months, I lapped up every moment of this experience of a lifetime: working in a greenhouse on the roof of the Exobiology building, which turned the already sweltering Californian summer into a sweat box that overheated my equipment; kicking back at the end of a long day with my colleagues at the golf course, watching burrowing owls darting in and out of their holes at dusk; and joining hundreds of NASA employees cheer in joy and relief in the parade ground, watching as the Curiosity rover touched down safely on Mars.

More than a decade later, and I may not be a NASA employee, I may not have found those ancient aliens, but those experiences helped to shape my career. No longer content to slave away in a sweaty greenhouse lab for the sake of a paper just a handful of people will read, I became determined to share the joy and wonder of all science. I have taught children, educated and entertained through broadcast TV, and now write to inspire others to love science as much as I do. I believe that my academic history, tipped by those gold-edged months at NASA, help to lend my work a sprinkling of credibility.

Recently, I was thrilled when I was recruited as writer for an ambitious new video from SciShow, intertwining the stories of Thad Roberts, the man who stole moon rocks from NASA, and Joseph Gutheinz, the ex-special agent turned lawyer and educator, who has dedicated his life to getting them back. I knew that, with my personal experience at NASA, I’d be able to bring authenticity to the story. What I didn’t expect, was that my vested interests would end up making my job much harder.

Sex on the Moon

Thad Roberts was a NASA intern, just like I had been. Even more privileged, in fact, because his intership program lasted far longer, and represented a significant stepping stone on the road to becoming an astronaut. Roberts had been ejected from the Mormon church after admitting extramarital sex, but subsequently worked hard to redeem himself, studying a slew of sciences and accruing and impressive portfolio of volunteering and charitable activities. His fellow interns described him as something of a charismatic eccentric. However, in 2002, during his third intern tour at the Johnson Space Center, Roberts’ eccentricity sent him spiralling off the tracks. Perhaps his morals had always been a little wonky - it later transpired that he was stealing fossils from the natural history museum where he volunteered - but the heist he planned and executed was the most audacious NASA had ever seen.

NASAs moon rocks, returned to Earth by the Apollo astronauts between 1969 and 1972, are considered national treasures, and the vast majority of the 300+kg are kept under strict two-party lock and key at the Lunar Vault at the Johnson Space Center. But the point of these rocks is to be studied, and at any one time small batches of the rocks are lent out to researchers around the world and within NASA itself. It’s here that Thad Roberts found his opportunity. He learned that the lunar scientist Everett Gibson had a safe inside his office that contained these research speciments. Sure, the safe was locked, and so was the office, but it was a much easier prospect that breaking into the main lunar vault.

So, in the summer of 2002, with the help of an internet whizz from Utah, and two other female interns who had fallen under his spell, Roberts cracked the code on Gibson’s lab and stole the entire safe. They took it back to a Motel, broke into it with power tools, and discovered inside just over 100g of lunar samples from every Apollo mission, as well as a heap of martian meteorites.

Roberts and his cronies hadn’t risked discovery for nothing. Before the theft had even taken place, they had identified a buyer - a Belgian mineral collector who had offered them $100,000 for their samples. Owning Apollo moon rocks is illegal, but that was still far below the going rate on the black market, which numbers into the millions. Unfortunately for Roberts, his Belgian knew of the illegality of the sale, and acted on his conscience, involving the FBI. So when the group turned up to an Orlando restaurant to make the sale, the FBI were waiting for them.

All of Everett Gibson’s samples were recovered, but their scientific value had been slashed. Lunar samples are normally handled in extremely controlled environments, to prevent them being contaminated by Earth’s air, water, and biology. But in breaking the chain of custody that began the moment Neil Armstrong picked these rocks from the surface of the moon, there was no knowing what damage Roberts had done. He claimed to have laid them out on the bed of their hotel and had sex with his girlfriend on top of them, so they could have ‘sex on the moon’ (although FBI photos later showed a perfectly made bed - making this tale either a fiction or the most disappointing round of intercourse anyone has ever seen). There were even reports of the group having licked the samples. Regardless, even with their handling, the moon rocks had been irrevocably contaminated, and would no longer be of any use to science. Not only that, but the safe had also contained Everett Gibson’s notebooks, containing more than 30 years of research. Those notebooks were never found.

Roberts was given 10 years in a federal prison after being charged with the theft of some $32 million of luanr material, and effectively shutting down a government department. The girls pled guilty but got away with probation. And the internet whizz who arranged the sale got 3.5 years. He says it saved him from a dissolute life of drug abuse.

Stolen Moon Rocks Taste Bad

It’s an incredible story, and SciShow were not the first to be inspired to tell it. Roberts’ dramatised exploits were the subject of the book ‘Sex on the Moon’ by Ben Mezrich (who also wrote the book on which the Social Network is based). But in the two decades since it had happened, Roberts and his accomplice have been released from prison, and forged new lives. Court documents have become available (although naturally not readily available!). I was excited to get my teeth into the research, and reached out to every contact I could find related to the story.

But honestly, what I found left a bit of a nasty taste in my mouth.

I think it was a mistake to read Ben Mezrich’s book first. Casting Roberts as the protagonist, the story hails him as he must have surely seen himself - a charismatic, fun, enviable, eccentric leader among his peers. A James Bond type, bewitching and intriguing all those who came within his influence. Even when covering his time in prison, the dramatisation describes how Roberts converted his fellow inmates to physics students, and single-handedly pioneered a successful astronomy club while teaching himself quantum physics and penning a book. It was so sickeningly sycophantic, so blithely uncritical, such a glorification of the man and his actions, that I found myself repelled.

Then, there was the contact I tried to make with Roberts himself. He’s more than a decade out of prison now, and obviously keen to put the events of that time behind him. He never responded to any of my requests for comment on any of his social media platforms. But he hasn’t hidden from the limelight. Far from it. He now bills himself as an academic speaker, an authority on theoretical physics and quantum mechanics. He has published videos and writings that assert his opinions on the subject with the self-assurance of a tenured physics professor, despite, as far as I could ascertain, never actually completing a degree. As someone who has always battled with self-assurance, I found it egotistical, belittling, and misleading. I consider it a kind of academic fraud.

Thad Roberts was a NASA intern. I was a NASA intern. Thad Roberts had the potential to realise his dreams of becoming an astronaut, but threw them all away on the promise of $100k. And now, he doesn’t even seem to show remorse, continuing to mis-sell himself on the academic stage. I had the potential to continue as a NASA scientist but chose a different path. A lot of soul searching went into that choice, and I still doubt myself on a daily basis. At times I can almost feel my self-doubt holding me back. And I haven’t served jail time for defrauding NASA, or continue to defraud the public.

Thad Roberts’ heist may be worthy of a James Bond storyline, but the man himself falls far, far short.

The Other Side of the Story

Thankfully, the NASA heist wasn’t the only tale I had to work with for the SciShow video. I also traced the eventful career of Joseph Gutheinz on his one-man quest to recover stolen moon rocks. He actually wasn’t involved in the Roberts heist, having left NASA a couple of years before, but his story is nevertheless a compelling one.

A military man, he became an investigative agent for the US department of transport, then the FAA, and eventually NASA. There, he investigated fraud cases that cost the agency millions, kept close tabs on the Russians, an even helped bring an astronaut impersonator to justice. But it was Operation Lunar Eclipse, and the recovery of Honduras’ moon rock, that really launched his moon rock hunting career.

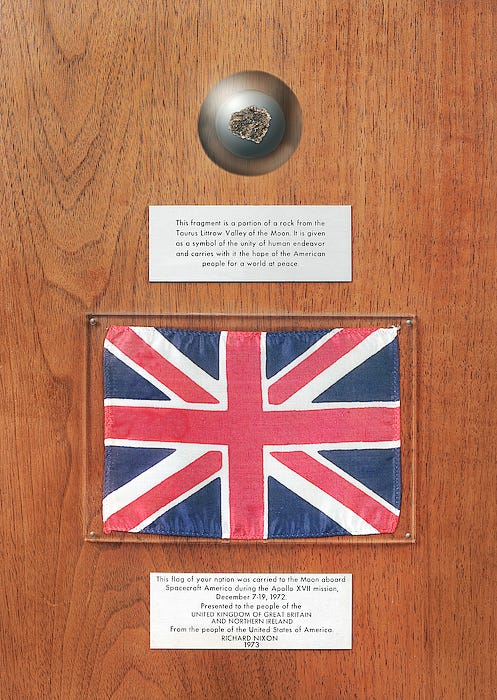

Because, as well as the hundreds of kilos of moon rocks that are safely locked away, and the handfuls that are loaned out to scientists every year, there are also moon rocks that belong to the people of every nation. After Apollos 11 and 17, the US government gifted so-called ‘Goodwill Rocks’ to the people of every 135 countries and all 50 US states. These amounted to a few grains of dust or a pea sized piece of lunar material, encased in a resin ball to make it look bigger and mounted on a plaque bearing the recipients’ flag. The idea was that these rocks would be displayed in public museums etc, as an inspiration and a testament to the Earth’s (read: America’s) ambition and achievement (ego, much?).

The problem was, many of these Goodwill rocks have since gone missing. Not every nation values them as Americans do. The recipients’ goverments didn’t them as national treasures, but rather trophies of their own importance. Governors held on to them, or discharged them into the sea of bureaucracy. Some were intentionally sold. Some were stolen. Some were simply misplaced.

Operation Lunar Eclipse, led by Gutheinz, was a sting operation to recover an unknown central American goodwill rock. It turned out to be Honduras’ Apollo 17 rock. Gutheinz set up a fake estate sales business and advertised for moon rocks, hoping to attract fraudsters selling replicas. But his first bite turned out to be the real thing. With the monetary help of ex-presidential candidate Ross T Perot, Gutheinz arranged the sale for $5 million, and moved in to catch the criminal. Honduras got its rock back, Perot never parted with a cent, and the perp got off without charge, since it was ruled that he never really owned it in the first place.

Gutheinz left NASA, but continued to be obsessed with moon rocks. He taught classes in criminal investigation at a university and community college, and enlisted his students to figure out which other goodwill rocks were missing, and try to track them down. Together, they recovered more than 70, in governors offices, in forgotten storage facilities, and in the hands of people who, like Thad Roberts, thought they could make a tidy profit.

There are still plenty of moon rocks missing, and Gutheinz has a wish-list for the ones he still wants to hunt. He was one of our story’s protagonists that I did manage to interview. I found him warm, proud of his work but not prideful or boastful. He was excited about the task, and keen to credit his students’ contributions. His search is perhaps a little esoteric, since it’s clear that most countries don’t value moon rocks as much as the US does. But it’s harmless, and optimistic, the work of someone who’s not afraid to put in the effort for something he cares about. I think we could all use a little of that attitude.

You can watch the SciShow video here:

Afterword

It turns out, my ambition to write a reflection and to update you on my discoveries around the internet and the outside world was characteristically overoptimistic. It’s taken me longer than I would have liked to write about moon rocks, partly because it’s taken a long time to get my jumbled thoughts and feelings into some kind of coherent order. But here we are.

Going forward, I’ll follow each newsletter with a little afterword like this, with anything interesting or relevant, but make no promises about its usefulness or coherence. Who knows if anyone’s still reading at this point?!

Anyway, here’s a few things I want to tell you:

A video recently went viral about whether we’ve peed during every second of the day. Hank Green said it was a young person question, I thought it was a maths question. So I did the maths and made a video. You can check it out here:

I recently finished the three book Mistborn series by Brandon Sanderson. It was my first foray into the Cosmere, and I adored it. It was an epic piece of worldbuilding, with a solid physical basis for the story and mythology. I don’t think I’ve ever read a fantasy writer that puts as much effort into the world itself as into the characters. Big recommend.